This post originally appeared at https://www.badgerinstitute.org/metrics-show-free-market-reforms-lead-to-broad-prosperity-in-wisconsin/

Our earlier report showed that Wisconsin’s economy has been delivering a strong overall performance. However, it left unanswered whether the gains are broadly distributed and whether Wisconsin’s economy is coming through for workers.

Fortunately, as we will show, Wisconsinites have been sharing broadly in the state’s prosperity. Wisconsin’s economy is thriving under free market reforms, many aided by Badger Institute research and advocacy.

Our prior study investigated net migration to Wisconsin, state labor force measures, business formation, and economic freedom. This study expands the inquiry, looking at some new measures such as poverty and income inequality and examining labor force participation and entrepreneurship in greater detail.

The overall conclusions: Wisconsin’s economy outperforms the nation on a myriad of measures. Although free market-oriented reforms can raise concerns about equity from some quarters, our results indicate that Wisconsin’s economy is delivering superior outcomes. These results add further evidence that the state’s long-term commitment to competitive reforms is paying dividends today.

Labor Force Participation

Wisconsinites work, with stronger participation in the labor force than the national average.

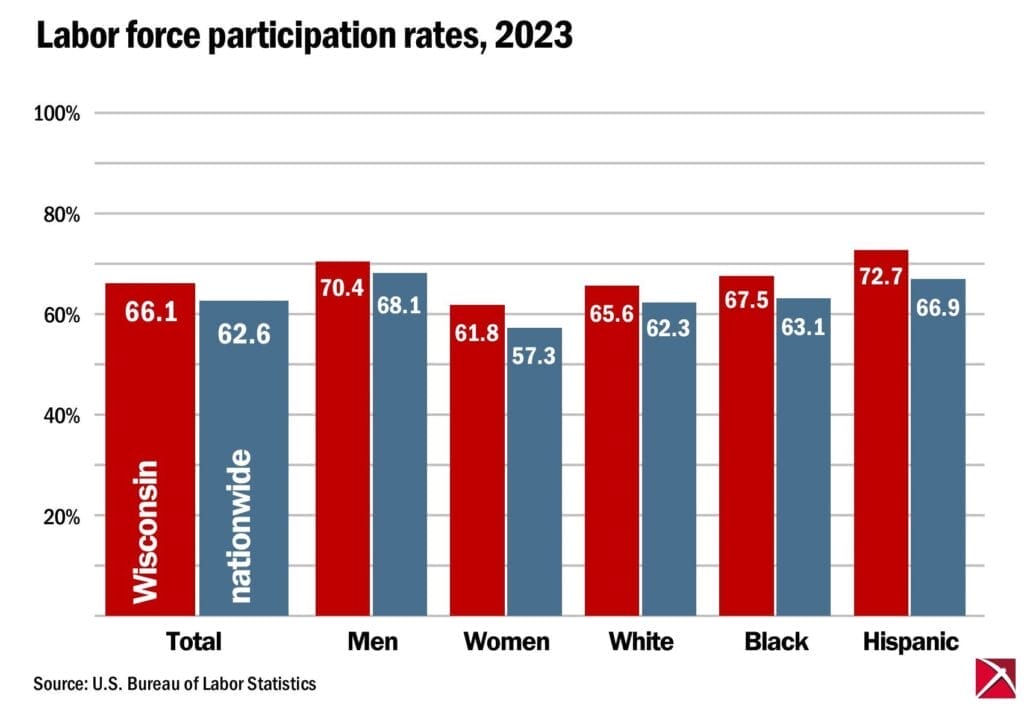

As displayed in Figure 1, the labor force participation rate for Wisconsin exceeded the national average last year. This figure, provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, represents the total share of adults working or looking for work. Wisconsin’s outperformance applies across race and gender lines.

For example, 61.8% of Wisconsin women participate in the labor force while 57.3% do nationally. Labor force participation is 67.5% for Black Wisconsinites, compared with 63.1% nationally. For Hispanics, the numbers are 72.7% among Wisconsinites compared with 66.9% nationally.

The pattern of greater labor force participation extends across worker age groups (Figure 2). For example, more than 55% of Wisconsin teenagers work, well above the 37% figure for the nation. Among the oldest workers, almost 17% of those over 65 in Wisconsin participate in the labor force while only about 8% do so nationally.

Poverty levels

Wisconsin has low levels of poverty, no matter how it’s measured.

The U.S. Census Bureau uses an official poverty measure and a supplemental measure. These statistics provide the national picture and allow state-to-state comparisons.

The official poverty measure dates back to 1963. It essentially considers a family to be in poverty if its before-tax cash income is less than three times the cost of a minimum food diet (adjusted for family size). This poverty measure is adjusted each year for inflation using the Consumer Price Index.

The Supplemental Poverty Measure was developed to more accurately reflect the degree of economic hardship experienced by households. It accounts for government assistance and for federal and state taxes. The SPM also considers geographic variation in housing costs and home ownership status to set its poverty threshold.

Table 1 displays data for both measures of poverty across three different age groups (under 18, 18 to 64, and 65 and older). Wisconsin had better performance than the national average for all of these groups from 2021 to 2023. In 50-state rankings by the official rate, Wisconsin had a Top Ten performance for low poverty in every age group except those under 18. For those over 65, Wisconsin had the second lowest SPM (7.8%) and the third lowest official rate (6.1%). Iowa had the lowest poverty measure on each of these indicators, while California and Louisiana had the highest rates. California ranked last among the states (that is, the highest percentage of people in poverty) in each of the measures of supplemental poverty.

Table 1: Different poverty rank and measures for Wisconsin, lowest state, highest state, and U.S. (2021-2023 average)

| Under 18 Official Poverty Rate | Under 18 Supplemental Poverty Rate | 18 to 64 Official Poverty Rate | 18 to 64 Supplemental Poverty Rate | 65 + Official Poverty Rate | 65 + Supplemental Poverty Rate | |

| WI Rank (1=lowest poverty rate) | 18 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| WI poverty rate | 11.6 | 5.2 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 7.8 |

| U.S. Poverty Rate | 15.1 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 13.0 |

| Lowest State Poverty Rate | 7 (Utah) |

3.6 (Nebraska) |

6.5 (Utah) |

5.4 (South Dakota) |

5.2 (Iowa) |

5.7 (Iowa) |

| Highest State Poverty Rate | 27.4 (New Mexico) |

15.4 (California) |

17.0 (Louisiana) |

15.0 (California) |

15.9 (Louisiana) |

18.2 (California) |

Income inequality

Wisconsin has little income inequality following pro-business free market reforms.

Those concerned about income inequality might worry that Wisconsin’s recent reforms have made Wisconsin an unequal state. However, that is not true. The state shows relatively low levels of income inequality following dramatic gains in levels of economic freedom and an improved tax climate relative to other states.

The most common measure of income inequality is the Gini Coefficient. This statistic measures the statistical variation of incomes across a given population, ranging from 0 (no income inequality, with all people’s incomes the same) to 1 (maximum inequality). If there is a large variation in incomes, the Gini Coefficient is large, and if there is little variation, it is small.

By this measure, Wisconsin is the sixth most equal state in the U.S., with a Gini Coefficient of 0.448. Coefficients for the 10 states with the lowest measured income inequality are shown in Table 2. Utah ranks the most equal with a Gini of 0.423, while the U.S. overall comes in at 0.483.

Table 2: 10 states with lowest level of income inequality (2023)

| State | Gini Coefficient |

| Utah | 0.423 |

| Idaho | 0.440 |

| New Hampshire | 0.445 |

| Iowa | 0.446 |

| Wyoming | 0.446 |

| Wisconsin | 0.448 |

| Alaska | 0.449 |

| Hawaii | 0.451 |

| Maine | 0.451 |

| Kansas | 0.452 |

| United States | 0.483 |

The 10 states with the highest Gini Coefficients are shown in Table 3. New York is the most unequal state, followed by Louisiana, Connecticut, Massachusetts and California. Our neighbor to the south, Illinois, comes in as the 43rd most unequal state, with a Gini Coefficient of 0.481.

Table 3: 10 states with highest level of income inequality (2023)

| State | Gini Coefficient |

| New Jersey | 0.479 |

| Texas | 0.479 |

| Illinois | 0.481 |

| Florida | 0.483 |

| Mississippi | 0.484 |

| California | 0.487 |

| Massachusetts | 0.488 |

| Connecticut | 0.495 |

| Louisiana | 0.497 |

| New York | 0.516 |

Business creation by county

Wisconsin’s counties create new businesses at a high rate.

In keeping with our earlier findings, Wisconsin is now well above the U.S. median for business formation. Forbes Advisor ranked Wisconsin the 14th best state to start a business in 2024i. In this ranking Wisconsin outpaced Midwestern peer states Illinois (ranked 28th), Iowa (31st), Michigan (40th), and Minnesota (43rd).

Figure 3 illustrates the percentage change in private business establishments between 2014 and 2022 for Wisconsin and its border states. Once again Illinois emerges as the laggard, experiencing a reduction of more than 4% in private businesses. Iowa’s private sector grew by a modest 12%, while growth was much stronger in Michigan (25.7%), Minnesota (22.2%), and Wisconsin (21.3%).

New business formation was widely distributed across Wisconsin’s 72 counties. Only four counties saw a decline in new private business creation: Florence, Oneida, Forest and Price. Kenosha County led the state in percentage increase in new private business establishments between 2014 and 2023, with an increase of more than 41%. Other leaders in new businesses established by percentage included Pierce, Walworth, Chippewa and Richland.

When measured by the number of new private businesses established, Milwaukee and Dane were the leaders, followed by Waukesha, Kenosha and Racine. Table 4 shows the top-performing counties.

Conclusion

Our previous study showed that the Wisconsin economy outperforms both neighboring states and the nation on unemployment, net migration, entrepreneurship, and economic freedom. In this study, we look at additional indicators and drill down further into others, reinforcing our conclusion: Wisconsin’s economy not only excels relative to its neighbors and the nation, but does so in ways that benefit workers and reduce economic hardship.

More Wisconsinites work, across all age and demographic groups, than the national average. Wisconsin’s economy produces low levels of poverty no matter how it’s measured and across all measured age groups. Free-market reforms in Wisconsin in recent years have not affected income inequality—in fact, on this measure too Wisconsin performs well. Wisconsin’s counties continue to provide an environment for the creation of private businesses at an impressive clip, suggesting that the entrepreneurial spirit is strong across the state.

These results suggest that free-market economic reforms advocated by groups such as the Badger Institute have created an environment where both businesses and workers can prosper.

Scott Niederjohn is a professor and the director of the Free Enterprise Center at Concordia University Wisconsin, and he is a visiting fellow of the Badger Institute.

Any use or reproduction of Badger Institute articles or photographs requires prior written permission. To request permission to post articles on a website or print copies for distribution, contact Badger Institute President Mike Nichols at mike@badgerinstitute.org or 262-389-8239.

var gform;gform||(document.addEventListener(“gform_main_scripts_loaded”,function(){gform.scriptsLoaded=!0}),document.addEventListener(“gform/theme/scripts_loaded”,function(){gform.themeScriptsLoaded=!0}),window.addEventListener(“DOMContentLoaded”,function(){gform.domLoaded=!0}),gform={domLoaded:!1,scriptsLoaded:!1,themeScriptsLoaded:!1,isFormEditor:()=>”function”==typeof InitializeEditor,callIfLoaded:function(o){return!(!gform.domLoaded||!gform.scriptsLoaded||!gform.themeScriptsLoaded&&!gform.isFormEditor()||(gform.isFormEditor()&&console.warn(“The use of gform.initializeOnLoaded() is deprecated in the form editor context and will be removed in Gravity Forms 3.1.”),o(),0))},initializeOnLoaded:function(o){gform.callIfLoaded(o)||(document.addEventListener(“gform_main_scripts_loaded”,()=>{gform.scriptsLoaded=!0,gform.callIfLoaded(o)}),document.addEventListener(“gform/theme/scripts_loaded”,()=>{gform.themeScriptsLoaded=!0,gform.callIfLoaded(o)}),window.addEventListener(“DOMContentLoaded”,()=>{gform.domLoaded=!0,gform.callIfLoaded(o)}))},hooks:{action:{},filter:{}},addAction:function(o,r,e,t){gform.addHook(“action”,o,r,e,t)},addFilter:function(o,r,e,t){gform.addHook(“filter”,o,r,e,t)},doAction:function(o){gform.doHook(“action”,o,arguments)},applyFilters:function(o){return gform.doHook(“filter”,o,arguments)},removeAction:function(o,r){gform.removeHook(“action”,o,r)},removeFilter:function(o,r,e){gform.removeHook(“filter”,o,r,e)},addHook:function(o,r,e,t,n){null==gform.hooks[o][r]&&(gform.hooks[o][r]=[]);var d=gform.hooks[o][r];null==n&&(n=r+”_”+d.length),gform.hooks[o][r].push({tag:n,callable:e,priority:t=null==t?10:t})},doHook:function(r,o,e){var t;if(e=Array.prototype.slice.call(e,1),null!=gform.hooks[r][o]&&((o=gform.hooks[r][o]).sort(function(o,r){return o.priority-r.priority}),o.forEach(function(o){“function”!=typeof(t=o.callable)&&(t=window[t]),”action”==r?t.apply(null,e):e[0]=t.apply(null,e)})),”filter”==r)return e[0]},removeHook:function(o,r,t,n){var e;null!=gform.hooks[o][r]&&(e=(e=gform.hooks[o][r]).filter(function(o,r,e){return!!(null!=n&&n!=o.tag||null!=t&&t!=o.priority)}),gform.hooks[o][r]=e)}});

Submit a comment

“*” indicates required fields

/* = 0;if(!is_postback){return;}var form_content = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘#gform_wrapper_21’);var is_confirmation = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘#gform_confirmation_wrapper_21’).length > 0;var is_redirect = contents.indexOf(‘gformRedirect(){‘) >= 0;var is_form = form_content.length > 0 && ! is_redirect && ! is_confirmation;var mt = parseInt(jQuery(‘html’).css(‘margin-top’), 10) + parseInt(jQuery(‘body’).css(‘margin-top’), 10) + 100;if(is_form){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).html(form_content.html());if(form_content.hasClass(‘gform_validation_error’)){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).addClass(‘gform_validation_error’);} else {jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).removeClass(‘gform_validation_error’);}setTimeout( function() { /* delay the scroll by 50 milliseconds to fix a bug in chrome */ jQuery(document).scrollTop(jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).offset().top – mt); }, 50 );if(window[‘gformInitDatepicker’]) {gformInitDatepicker();}if(window[‘gformInitPriceFields’]) {gformInitPriceFields();}var current_page = jQuery(‘#gform_source_page_number_21’).val();gformInitSpinner( 21, ‘https://e74sq7k37a8.exactdn.com/wp-content/plugins/gravityforms/images/spinner.svg’, true );jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_page_loaded’, [21, current_page]);window[‘gf_submitting_21’] = false;}else if(!is_redirect){var confirmation_content = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘.GF_AJAX_POSTBACK’).html();if(!confirmation_content){confirmation_content = contents;}jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).replaceWith(confirmation_content);jQuery(document).scrollTop(jQuery(‘#gf_21’).offset().top – mt);jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_confirmation_loaded’, [21]);window[‘gf_submitting_21’] = false;wp.a11y.speak(jQuery(‘#gform_confirmation_message_21’).text());}else{jQuery(‘#gform_21’).append(contents);if(window[‘gformRedirect’]) {gformRedirect();}}jQuery(document).trigger(“gform_pre_post_render”, [{ formId: “21”, currentPage: “current_page”, abort: function() { this.preventDefault(); } }]); if (event && event.defaultPrevented) { return; } const gformWrapperDiv = document.getElementById( “gform_wrapper_21” ); if ( gformWrapperDiv ) { const visibilitySpan = document.createElement( “span” ); visibilitySpan.id = “gform_visibility_test_21”; gformWrapperDiv.insertAdjacentElement( “afterend”, visibilitySpan ); } const visibilityTestDiv = document.getElementById( “gform_visibility_test_21” ); let postRenderFired = false; function triggerPostRender() { if ( postRenderFired ) { return; } postRenderFired = true; jQuery( document ).trigger( ‘gform_post_render’, [21, current_page] ); gform.utils.trigger( { event: ‘gform/postRender’, native: false, data: { formId: 21, currentPage: current_page } } ); gform.utils.trigger( { event: ‘gform/post_render’, native: false, data: { formId: 21, currentPage: current_page } } ); if ( visibilityTestDiv ) { visibilityTestDiv.parentNode.removeChild( visibilityTestDiv ); } } function debounce( func, wait, immediate ) { var timeout; return function() { var context = this, args = arguments; var later = function() { timeout = null; if ( !immediate ) func.apply( context, args ); }; var callNow = immediate && !timeout; clearTimeout( timeout ); timeout = setTimeout( later, wait ); if ( callNow ) func.apply( context, args ); }; } const debouncedTriggerPostRender = debounce( function() { triggerPostRender(); }, 200 ); if ( visibilityTestDiv && visibilityTestDiv.offsetParent === null ) { const observer = new MutationObserver( ( mutations ) => { mutations.forEach( ( mutation ) => { if ( mutation.type === ‘attributes’ && visibilityTestDiv.offsetParent !== null ) { debouncedTriggerPostRender(); observer.disconnect(); } }); }); observer.observe( document.body, { attributes: true, childList: false, subtree: true, attributeFilter: [ ‘style’, ‘class’ ], }); } else { triggerPostRender(); } } );} );

/* ]]> */

i https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/best-states-to-start-a-business/

The post Metrics show free-market reforms lead to broad prosperity in Wisconsin appeared first on Badger Institute.