This post originally appeared at https://www.badgerinstitute.org/local-government-regulations-push-price-of-a-wisconsin-roof-skyward/

Builders, economists cite rules, especially those on lot size, for affordability crisis, but point to solutions

Regulations imposed by local governments are being fingered as a costly — and reversible — contributor to $400,000 Wisconsin starter homes that are increasingly unattainable.

As one common council member in Middleton, Lisa Janairo, put it, “A lot of us would not be able to afford the houses we’re living in now if we were buying now.”

Price tag

How big a factor are regulatory costs?

Often cited is a groundbreaking 2021 study by the National Association of Home Builders based on surveys of land developers and residential builders: It pegged the direct costs of regulation as constituting 23.8 percent, on average, of the cost of a new single-family home.

On a $400,000 home, the cost of regulation would be $95,000.

The study split up the regulatory cost by different types of regulation: Fees and studies during land development add 3 percent, changes to building codes in the past 10 years add 6 percent, lot standards that go beyond the ordinary, such as large setbacks, add 2.3 percent.

The builders association vice president who did the 2021 study, Paul Emrath, said the point wasn’t to fault all regulations or codes, some of them necessary to good construction. Rather, said the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee-trained economist, “I was hoping it would make people a little more cautious before adding more.”

This was the third iteration of his study, Emrath said, and it came after the first two prompted a federal agency looking for more details to search the literature for comparable studies. It found none.

“There are some people on these zoning boards and city councils who are concerned about housing costs and want to do something about it,” he said. “This should give them some cover.”

Indeed, on an NAHB podcast last December, Washington County Executive Josh Schoemann said he thought the regulatory cost per house was “somewhere between $60- and $90,000” in Washington County. Schoemann, who in recent weeks announced he is running for governor, repeated the figure in January when interviewed by the Badger Institute. He noted that zoning codes have swelled and municipalities now impose requirements at a fine level of detail — “like matching mailboxes and matching light posts on every lot,” he said.

“We’re not talking about nickels and dimes here,” he said, “but dollars and ten-dollar bills.”

But if the NAHB study was meant to make officials cautious, caution can work to increase costs, too.

Steve DeCleene, president of Neumann Companies, the large Pewaukee-based developer, pointed to regulations regarding backfill as an example.

When a builder develops a subdivision, it isn’t the city that installs sewer lines — the developer does, building the cost into the price of homes, if he can, and eventually turning the infrastructure over to the city.

Sanitary sewers are built about 12 feet below the surface of streets, meaning a lot of material goes to backfilling the trench after the pipe is in place. What material? That’s a $10,000-per-lot question, said DeCleene — much cheaper if it’s simply the excavated dirt, much costlier if it’s trucked-in rock: “It’s a lot of stone.”

A municipality might demand trucked-in stone, however, to mitigate any risk of dirt settling and requiring later repairs to the fresh-laid pavement above.

“That’s where the incentives get perverse,” said DeCleene: Repaving might amount to perhaps a thousand dollars a lot, much less than the cost of rock backfill, but the cost of the rock doesn’t fall on the municipality. Unless a city is relentlessly focused on keeping costs down — DeCleene suggests a three-year deposit against pavement problems as a cheaper alternative to unnecessary rock backfill, for instance — then requirements pile up and make houses costly.

These are differences are in what builders call “means and methods” — the requirements that differ from one place to another. DeCleene praises Beaver Dam as an example of a city where the approval process is reasonably quick — meaning developers have to pay interest on borrowed money for less time before they can sell houses — and the means and methods are reasonable. This leads to new houses at lower prices than in, for example, Waukesha County.

To be clear, the land is cheaper near Beaver Dam than in the Waukesha County suburbs of Milwaukee. But “that’s the least of the problem,” says DeCleene, whose company has contributed to the Badger Institute.

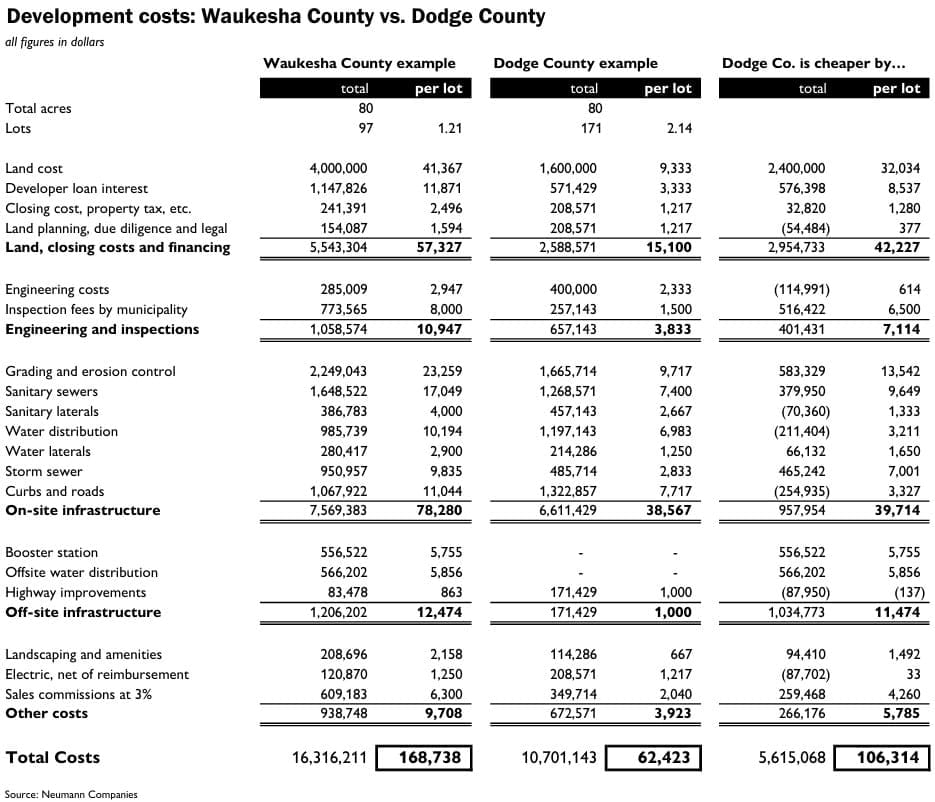

He offered examples of land development costs at projects in the two counties — one his company did in Dodge County and one for which he had accurate numbers in Waukesha County. The difference in the cost of land accounted for just over $14,000 of the $106,314 per-lot cost advantage the Dodge County project had.

The bulk of the difference is means and methods, and, of those means and methods, “the biggest is lot size, which gets down to zoning,” says DeCleene.

Between the two examples, each on 80 acres, the Waukesha County example saw costs spread over 97 lots, or 1.21 houses an acre, while the Beaver Dam example spread the costs over 171 lots, or 2.14 houses per acre — considerably less dense than the average of new home construction in Wisconsin since 2000.

The size of lots on a given tract of land is determined by a city’s zoning — rules on minimum lot sizes, minimum widths, required setbacks. Lot size affects how much land cost is built into each house, said Emrath, as well as how much footage of sewer, of pavement, of curbs, all of which a developer must recoup in the final sale if he hopes to remain in business. Since lot cost is related in lending to the cost of the structure on it, lot size governs how expensive a house will be built.

“My cost per foot of road doesn’t change much if I change the number of lots,” said DeCleene. The cost of lots and the houses to be built on them depends heavily on how many feet of sewer, street and curb are fronted by each lot. More mandated space between houses means more cost — a reality immediately clear to trick-or-treaters.

“You want to identify good land policy?” he said. “Drive around on Oct. 31 and see where the kids are.”

As DeCleene sees it, the problem is zoning codes that, by requiring large lots, prevent builders from putting up starter-priced houses. He doesn’t particularly fault local officials: “When you talk to people in a community, they want housing that’s more grand than their house,” he says. At public meetings about zoning and new developments, those who attend are neighbors whose land values are affected by what will be built.

“You know who doesn’t come out? The 100 people who are going to buy my homes. Why? Because they don’t even know who I am yet,” he says.

“I applaud public bodies that stand up to the people who only want million-dollar houses.”

Some municipal officials have a different take. DeCleene’s Waukesha County example is based on a development in northern Muskego. The mayor of Muskego, Rick Petfalski, replying by email, said that residents aren’t so much looking for grander houses on larger lots nearby but, rather, open space.

Rather than a large-lot or small-lot pattern, “The citizens would prefer ‘no-lot’ development,” he said. “Many people move to our community because of our great schools and safe community, but also because of the rural county feel. They enjoy seeing rolling countryside and farms.”

As Petfalski sees it, “developers are looking for changes that will increase their profits.” He said he doesn’t begrudge their success, but he opposes any state mandate for smaller lots, which he said would simply “pack more people into a smaller area (and) put more strain on services.”

But communities do have incentives to ease regulatory costs, too.

Beaver Dam knows it has a housing shortage “in almost every category,” said Trent Campbell, the city’s economic development director — including in what he calls “family housing,” the kind in the subdivision in DeCleene’s example.

“Our employers are telling us that one of the critical factors in finding employees is housing,” he said. “They have to find a place to live at a reasonable cost.”

For Beaver Dam, that meant approving the Neumann project on Ollinger Road where neat three- and four-bedroom houses on 70- by 133-foot lots — that’s a fifth of an acre — sell in the upper $300,000 range, which is about as low as builders say they can manage on new construction in Wisconsin. “We were very accepting of smaller lot sizes,” said Campbell.

He is careful to avoid criticizing anywhere else — “every community has got to decide what its needs and wants are, what its character is” — but he said a focus on removing regulatory barriers, from lot size rules to “check-the-box regulatory policies,” is doable.

“I don’t think it’s rocket science, but it certainly does take common sense and a fluidity,” he said.

Janairo, the Middleton council member, represents a district that includes a series of new subdivisions, including one, Redtail Ridge, that attracted attention for putting homes on small lots, some as small as tenth of an acre. Houses sold in the $400,000s and up — “not affordable, but attainable,” she said, and an outfall of Madison-area land costs.

Janairo said she didn’t hear pushback from neighbors over the small lots, perhaps because “it’s mostly single-family homes: People are much more accepting,” she said of single-family homes than of apartments.

Or perhaps it’s sympathy: The area on Middleton’s northwest side is home to many who moved to the Madison area in the past 10 years, drawn by jobs, and among such newcomers, “there has been a welcoming attitude toward new housing.”

DeCleene, for his part, says he isn’t arguing with municipalities that don’t want smaller lots, more reasonable regulation and more attainable homes. He’s a builder, not a politician: “I don’t persuade anybody. I find the spots where I don’t need to persuade them.”

But those spots aren’t easy to find, he says, because of a not-in-my-backyard attitude, and he sees that as pushing us toward eventually being a nation of renters.

“It’s the American dream to own a home,” he said, “and it’s at risk.”

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute.

Any use or reproduction of Badger Institute articles or photographs requires prior written permission. To request permission to post articles on a website or print copies for distribution, contact Badger Institute Marketing Director Matt Erdman at matt@badgerinstitute.org.

/* “function”==typeof InitializeEditor,callIfLoaded:function(o){return!(!gform.domLoaded||!gform.scriptsLoaded||!gform.themeScriptsLoaded&&!gform.isFormEditor()||(gform.isFormEditor()&&console.warn(“The use of gform.initializeOnLoaded() is deprecated in the form editor context and will be removed in Gravity Forms 3.1.”),o(),0))},initializeOnLoaded:function(o){gform.callIfLoaded(o)||(document.addEventListener(“gform_main_scripts_loaded”,()=>{gform.scriptsLoaded=!0,gform.callIfLoaded(o)}),document.addEventListener(“gform/theme/scripts_loaded”,()=>{gform.themeScriptsLoaded=!0,gform.callIfLoaded(o)}),window.addEventListener(“DOMContentLoaded”,()=>{gform.domLoaded=!0,gform.callIfLoaded(o)}))},hooks:{action:{},filter:{}},addAction:function(o,r,e,t){gform.addHook(“action”,o,r,e,t)},addFilter:function(o,r,e,t){gform.addHook(“filter”,o,r,e,t)},doAction:function(o){gform.doHook(“action”,o,arguments)},applyFilters:function(o){return gform.doHook(“filter”,o,arguments)},removeAction:function(o,r){gform.removeHook(“action”,o,r)},removeFilter:function(o,r,e){gform.removeHook(“filter”,o,r,e)},addHook:function(o,r,e,t,n){null==gform.hooks[o][r]&&(gform.hooks[o][r]=[]);var d=gform.hooks[o][r];null==n&&(n=r+”_”+d.length),gform.hooks[o][r].push({tag:n,callable:e,priority:t=null==t?10:t})},doHook:function(r,o,e){var t;if(e=Array.prototype.slice.call(e,1),null!=gform.hooks[r][o]&&((o=gform.hooks[r][o]).sort(function(o,r){return o.priority-r.priority}),o.forEach(function(o){“function”!=typeof(t=o.callable)&&(t=window[t]),”action”==r?t.apply(null,e):e[0]=t.apply(null,e)})),”filter”==r)return e[0]},removeHook:function(o,r,t,n){var e;null!=gform.hooks[o][r]&&(e=(e=gform.hooks[o][r]).filter(function(o,r,e){return!!(null!=n&&n!=o.tag||null!=t&&t!=o.priority)}),gform.hooks[o][r]=e)}});

/* ]]> */

Submit a comment

“*” indicates required fields

/* = 0;if(!is_postback){return;}var form_content = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘#gform_wrapper_21’);var is_confirmation = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘#gform_confirmation_wrapper_21’).length > 0;var is_redirect = contents.indexOf(‘gformRedirect(){‘) >= 0;var is_form = form_content.length > 0 && ! is_redirect && ! is_confirmation;var mt = parseInt(jQuery(‘html’).css(‘margin-top’), 10) + parseInt(jQuery(‘body’).css(‘margin-top’), 10) + 100;if(is_form){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).html(form_content.html());if(form_content.hasClass(‘gform_validation_error’)){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).addClass(‘gform_validation_error’);} else {jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).removeClass(‘gform_validation_error’);}setTimeout( function() { /* delay the scroll by 50 milliseconds to fix a bug in chrome */ jQuery(document).scrollTop(jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).offset().top – mt); }, 50 );if(window[‘gformInitDatepicker’]) {gformInitDatepicker();}if(window[‘gformInitPriceFields’]) {gformInitPriceFields();}var current_page = jQuery(‘#gform_source_page_number_21’).val();gformInitSpinner( 21, ‘https://e74sq7k37a8.exactdn.com/wp-content/plugins/gravityforms/images/spinner.svg’, true );jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_page_loaded’, [21, current_page]);window[‘gf_submitting_21’] = false;}else if(!is_redirect){var confirmation_content = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘.GF_AJAX_POSTBACK’).html();if(!confirmation_content){confirmation_content = contents;}jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).replaceWith(confirmation_content);jQuery(document).scrollTop(jQuery(‘#gf_21’).offset().top – mt);jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_confirmation_loaded’, [21]);window[‘gf_submitting_21’] = false;wp.a11y.speak(jQuery(‘#gform_confirmation_message_21’).text());}else{jQuery(‘#gform_21’).append(contents);if(window[‘gformRedirect’]) {gformRedirect();}}jQuery(document).trigger(“gform_pre_post_render”, [{ formId: “21”, currentPage: “current_page”, abort: function() { this.preventDefault(); } }]); if (event && event.defaultPrevented) { return; } const gformWrapperDiv = document.getElementById( “gform_wrapper_21” ); if ( gformWrapperDiv ) { const visibilitySpan = document.createElement( “span” ); visibilitySpan.id = “gform_visibility_test_21”; gformWrapperDiv.insertAdjacentElement( “afterend”, visibilitySpan ); } const visibilityTestDiv = document.getElementById( “gform_visibility_test_21” ); let postRenderFired = false; function triggerPostRender() { if ( postRenderFired ) { return; } postRenderFired = true; gform.core.triggerPostRenderEvents( 21, current_page ); if ( visibilityTestDiv ) { visibilityTestDiv.parentNode.removeChild( visibilityTestDiv ); } } function debounce( func, wait, immediate ) { var timeout; return function() { var context = this, args = arguments; var later = function() { timeout = null; if ( !immediate ) func.apply( context, args ); }; var callNow = immediate && !timeout; clearTimeout( timeout ); timeout = setTimeout( later, wait ); if ( callNow ) func.apply( context, args ); }; } const debouncedTriggerPostRender = debounce( function() { triggerPostRender(); }, 200 ); if ( visibilityTestDiv && visibilityTestDiv.offsetParent === null ) { const observer = new MutationObserver( ( mutations ) => { mutations.forEach( ( mutation ) => { if ( mutation.type === ‘attributes’ && visibilityTestDiv.offsetParent !== null ) { debouncedTriggerPostRender(); observer.disconnect(); } }); }); observer.observe( document.body, { attributes: true, childList: false, subtree: true, attributeFilter: [ ‘style’, ‘class’ ], }); } else { triggerPostRender(); } } );} );

/* ]]> */

The post Local government regulations push price of a Wisconsin roof skyward appeared first on Badger Institute.