This post originally appeared at https://www.badgerinstitute.org/criminal-enforcement-of-marijuana-laws-uncommon-in-wisconsin/

Incarceration for cannabis-only crimes becomes still rarer, prison almost nonexistent

Many counties in Wisconsin have essentially decriminalized the possession or sale of marijuana, and relatively few people who are charged criminally in other counties are ever incarcerated. More than half of Wisconsin’s counties — including some with more than 100,000 residents — had no more than 20 marijuana-only criminal charges in 2022. Some counties had none at all.

There are approximately 5.8 million people in Wisconsin and more than 830,000 use marijuana, also known as cannabis, each year.1 But in 2022, only 2,289 individuals were charged with a cannabis offense and had committed no more serious crimes.

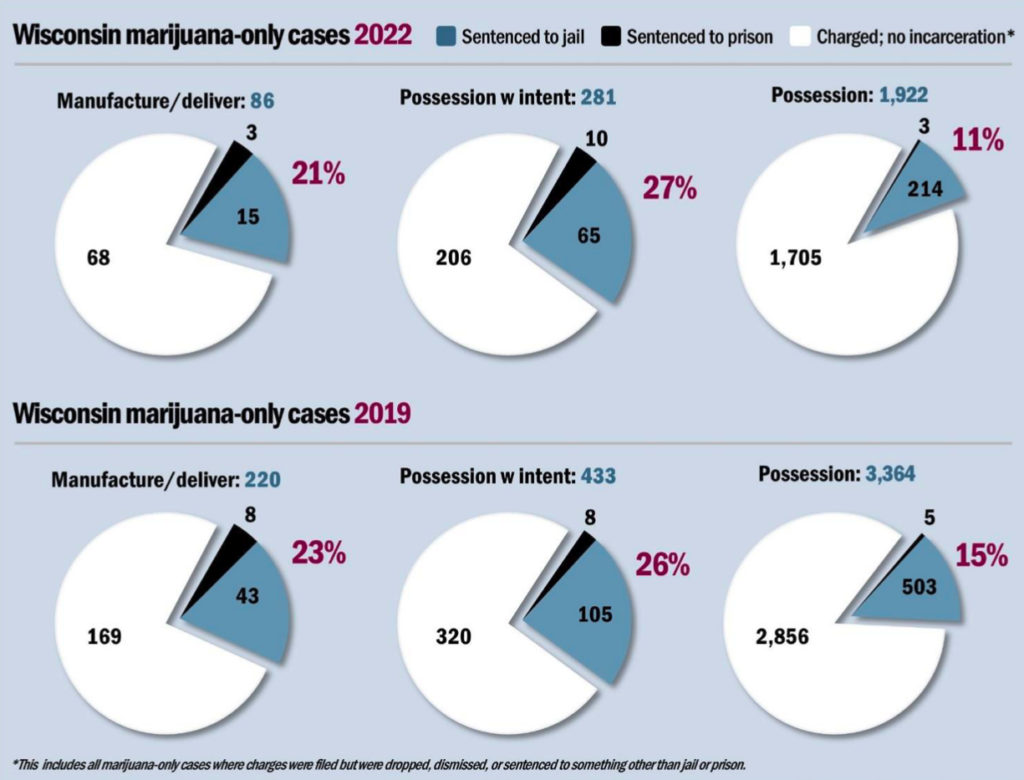

It is increasingly rare for such a charge to result in incarceration. Only 16 Wisconsinites were sentenced to prison — by definition more than a year in jail — for a cannabis-only criminal offense in 2022. Another 294 were sentenced to less than a year in jail. That means only 13.5% of all cannabis charges and 11.3% of possession offenses resulted in time in a prison or jail cell.

Wisconsin is seriously considering proposals that would allow the medical use of cannabis — a step that has preceded adult-use legalization in other states.2 A few years ago, a Badger Institute report explored how frequently Wisconsin was enforcing its law prohibiting marijuana.3 In this report, we wanted to provide Wisconsin’s leaders and citizens with a more comprehensive analysis conducted after the pandemic and legalization in more neighboring states.

The Badger Institute worked with Court Data Technologies — a Madison firm that analyzes Wisconsin court data — to compile data on the number of charges being brought for cannabis-only offenses and their sentencing outcomes.4

Criminal charges are rare in most parts of Wisconsin

More than half of the state’s counties — 37 out of 72, including some large counties — had no more than 20 cannabis-only criminal charges in 2022. Twenty of those 37 counties had fewer than 10 cannabis-only criminal charges.5 And in two — Crawford and Florence — no charges were brought at all.

Washington County, for example, home to almost 140,000 people, had only 12 cannabis-only criminal charges in 2022, eight for possession and four for possession with intent to deliver. La Crosse County, with more than 120,000 residents, had only 16 cannabis-only criminal charges, 14 for possession and two for possession with intent to deliver.

Even Milwaukee County, which has more than 918,000 residents, had only 43 cannabis-only criminal charges in 2022.

As we discuss below, enforcement of Wisconsin’s cannabis laws is down across the state, but this charging data shows that the severity of this reduction is not consistent across counties.

Incarceration for cannabis offenses

In Wisconsin in 2022, 2,289 individuals were charged with a cannabis offense and had committed no more serious crimes. It is increasingly rare for such a charge to result in incarceration. Only 13.5% of all cannabis charges and 11.3% of possession offenses resulted in that type of punishment. Among those who are incarcerated, a short jail sentence is significantly more likely, with 294 individuals receiving a jail sentence compared to only 16 being admitted to a state prison.

Zooming into the county data again we see a similar story with incarceration as we do with charging. In 21 of Wisconsin’s counties, not a single person was sentenced to incarceration for a cannabis offense, and another 13 counties sent only one person to prison or jail. Wisconsin prosecutors and judges throughout a large swath of the state have effectively ended incarceration for the possession, distribution, and manufacture of marijuana even without a formal legal or policy change. In 34 counties, or almost 50% of them, citizens can expect to receive no more than a fine or probation for violating existing cannabis laws — because only 13 people in those 34 counties were sentenced to any form of incarceration.6

Analyzing the county data for the most serious punishment only — a prison sentence — reveals that 83% of counties in the state did not impose that form of punishment on anyone during 2022. Only Brown, Sauk and Manitowoc counties imprisoned more than one person for a cannabis offense. Brown County not only is an outlier for 2022, but our historical data shows that it has sent the most individuals to state prison for cannabis offenses since 2017.

What has changed since 2019?

Since the Badger Institute’s last report on cannabis enforcement, we were able to secure three new years of data, and we wanted to explore how things might or might not have changed. Readers should remember that there were severe and unprecedented events — a pandemic, an economic shutdown, and a near- total end to criminal case processing — that will surely have affected all three years of this more recent data.7 An in-depth analysis of this and data from other sources reveals five conclusions:

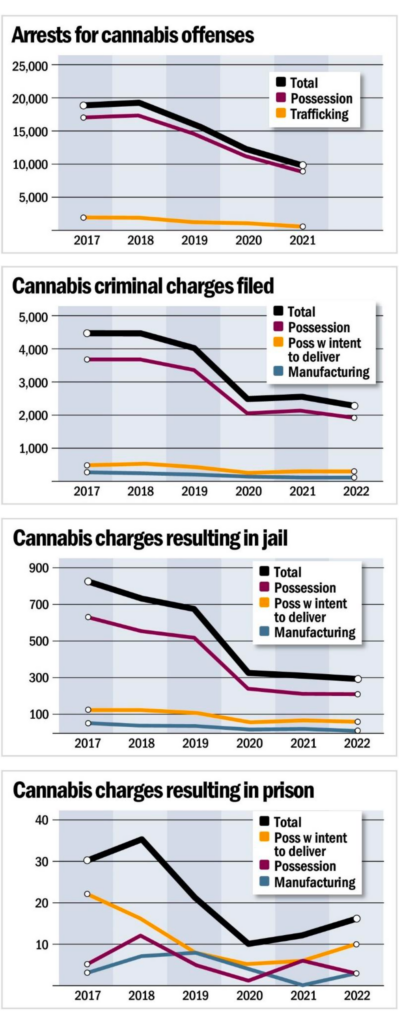

- All components of the criminal justice system have reduced their focus on cannabis offenses even though we know that cannabis use has increased in the Badger State, with the share of Wisconsinites 12 and older who’ve used in the past year increasing from 14.6% in 2018 to 16.6% in 2021 and monthly use rising from 9.1% to 11.1%.8 Law enforcement is making fewer arrests,9 prosecutors are filing fewer charges, and judges are sentencing fewer people to time in a state prison or local jail.

- An individual’s likelihood, once charged, of being incarcerated for a cannabis offense is essentially unchanged since 2019 (see charts above) on a percentage basis. There has been a small but not statistically significant reduction in the proportion of cases resulting in incarceration. In 2019, 4,028 people were charged, and 696 were sentenced to any form of incarceration. In 2022, 2,289 were charged, and 310 were sentenced any form of incarceration.

- Jail sentences for cannabis offenses declined significantly in 2020 and have not started increasing again while prison sentences have begun to rise (driven by possession with intent to deliver charges) but are still rare: 16 people sentenced to prison in 2022, up from 10 in 2020 but down from 21 in 2019.10

- Wisconsin continues to impose prison time for offenses involving other drugs, and drug offenses continue to be a substantial contributor to the state’s prison admissions.11

- Three jurisdictions — Milwaukee County, the City of Kenosha, and Stevens Point — formally decriminalized cannabis since our prior report, but those actions alone could not have caused the reduced focus on enforcing the state’s cannabis laws in the statewide data we compiled.12

Does geography matter?

We were also able to expand the analysis backward to include the data from 2017 and 2018. That historical data reveals that the overall reduced focus on enforcing cannabis crimes appeared to start in 2019, was accelerated in 2020 (likely because of the pandemic), and has continued over the past two years. This means that this de-prioritization across the justice system is likely not caused solely because of the pandemic. Therefore, we wanted to explore two additional factors that might be impacting how frequently and severely officials are enforcing the state’s current cannabis laws.

Urban versus rural

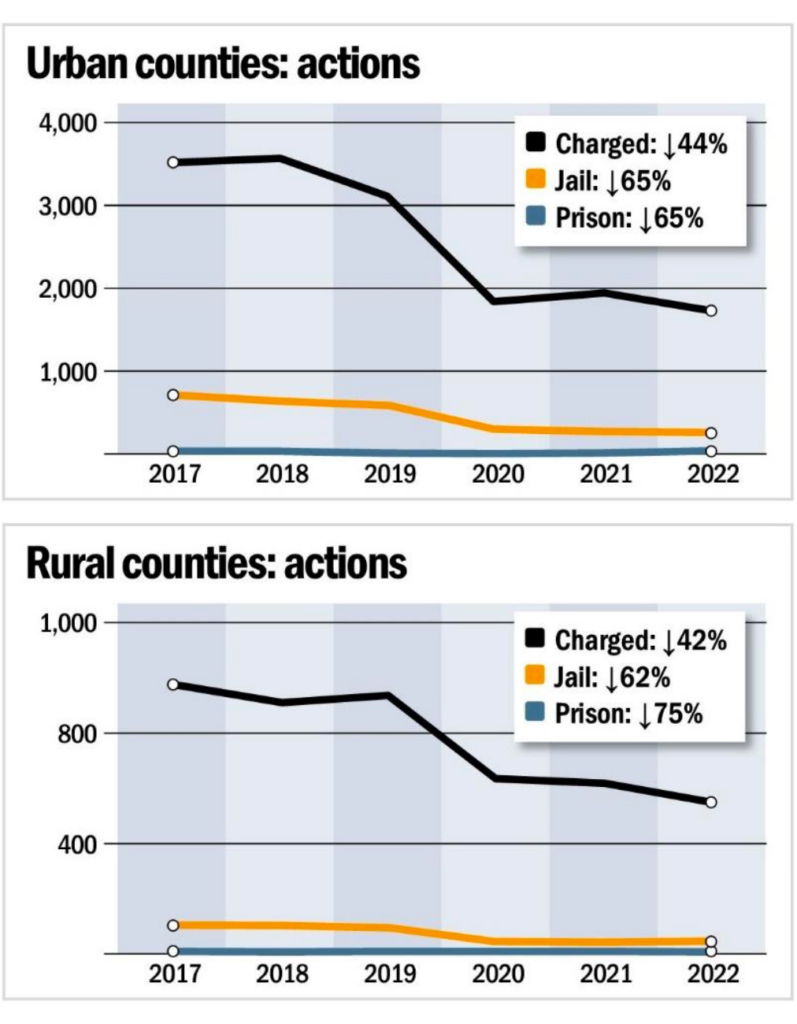

One of our initial hypotheses after reviewing the data was that this continued trajectory toward de facto decriminalization of cannabis in Wisconsin is being driven by more urban areas of the state, since all the areas adopting formal, legal decriminalization were more metropolitan. We secured county-by-county data in addition to statewide data to explore this potential factor and classified counties based on their designation by the United State Census Bureau.13

This segmentation of data revealed that both urban and rural counties are undergoing a similar downward trend in enforcement. The only outlier is charges of possession with intent to distribute, which have remained effectively unchanged in rural areas. The overall reduction in rural counties occurred because of a complete cessation of the enforcement of the statute prohibiting the manufacture or delivery of cannabis and a reduction in low-level possession enforcement equal to the overall reductions. While 86 were charged with manufacture in 2017, none were in 2022, and while 842 were charged with simple possession in 2017, 499 were in 2022. In rural counties, two were sentenced to prison for manufacture in 2017, while none were in 2022.

The first of these two trends is more likely than not a shift toward charging manufacturing or delivery as possession with intent to distribute rather than a decision to not enforce the laws against such conduct.14 A similar departure between the three types of cannabis offenses is not seen in urban counties. In sum, urban counties continue to progress toward the practical decriminalization of all cannabis offenses while rural counties are more likely to reduce only their enforcement of low-level possession.

Bordering a state with cannabis legalization

The second factor that we wanted to explore was how cannabis legalization by states that border Wisconsin might impact enforcement in border counties. Michigan and Illinois both legalized cannabis and established regulated markets during the years for which we secured data. Eleven Wisconsin counties border either of these two states.15

| Border Counties | Non-Border Counties | |

| Criminal Charges |  28% 28% |

44% 44% |

| Prison Sentences |  100%16 100%16 |

12% 12% |

| Jail Sentences |  39% 39% |

63% 63% |

An analysis of the data reveals that neighboring states legalizing cannabis does not result in increased enforcement or accelerate the practical decriminalization of cannabis offenses. In fact, our data shows that border counties saw less of a reduction in the number of criminal charges and jail sentences imposed for cannabis offenses. Nothing in our data indicates that recent legal changes in Minnesota should alter that conclusion.

Estimated prison cost savings for Wisconsin

Wisconsin’s prison population has declined by 13% since 2019, and there are now just over 20,600 individuals imprisoned in the Badger State.17 We do not know what percentage of this population snapshot is there for cannabis offenses, given the limited data provided by the Department of Corrections (DOC), but we do know that only a small percentage (0.23%) of the state’s prison admissions are solely for a cannabis offense.18 Cost data from the DOC and court records allow us to estimate that a policy change that fully ends the criminalization of cannabis in the Badger State would save the state approximately $600,000 in prison costs and $67,000 in supervision costs annually.19 While governments should always seek to utilize taxpayer resources for their highest value purpose, these minimal cost savings would account for only 0.04% of the state’s total corrections budget for fiscal year 2023.20

Lacking criminal justice data still prevents us from providing an estimate as to the potential cost savings of cannabis to other parts of the criminal justice system, including jails, police departments, prosecutors, public defenders and courts. These government agencies lack the necessary transparency and data reporting to calculate any good faith estimate that would be more than mere conjecture. But given that cannabis charges account for 4.3% of all charges brought in the state, we can assume that those savings would be more significant than the corrections savings — but likely still minimal in nature.

Jeremiah Mosteller is an attorney and criminal justice policy expert who serves as a policy director at Americans for Prosperity and a visiting fellow at the Badger Institute.

1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023), available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/state-reports; United States Census Bureau, Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022, United States Census Bureau (2022), available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html/.

2 Scott Bauer, Wisconsin GOP lawmakers working on medical pot legalization, Associated Press (2023), https://apnews.com/article/wisconsin-medical-marijuana-legalization-republicans- 92a5764d72a54914ecee54b37d6e8B13b; National Conference of State Legislatures, State Medical Cannabis Laws, National Conference of State Legislatures (2023), https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-medical-cannabis-laws.

3 Julie Grace, Few marijuana offenders in prison, Badger Institute (2021), https://www.badgerinstitute.org/few- marijuana-offenders-in-prison/.

4 For space reasons we will not be providing an endnote for every instance where we utilize our data, and only external sources will be cited in the endnotes.

5 This analysis was confined to marijuana-related criminal charges issued in circuit courts throughout the state. It does not include marijuana-related municipal ordinance violations that could have resulted in a forfeiture, nor does it include noncriminal citations for ordinance violations handled by a district attorney’s office, such as those issued by state agencies or sheriff’s departments.

6 I do not intend to insinuate that the imposition of a fine or probation instead of incarcerating is not a punishment. Prior research makes clear that these less severe forms of punishment cause major disruptions to people’s lives and restrict their liberty in ways that can serve as more appropriate accountability in certain cases.

7 For more details on the impact of the pandemic on criminal case processing you can read one of my prior analysis of criminal case court backlogs. See Jeremiah Mosteller, Courts clogged, Badger Institute (2022), https://www.badgerinstitute.org/diggings/courts-clogged/.

8 The percentage of residents in Wisconsin using cannabis has increased across the data for annual (14.62% to 16.62%) and monthly (9.05% vs. 11.11%) use. See Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, supra note i.

9 Federal Bureau of Investigations, Crime Data Explorer, Federal Bureau of Investigations (2023), https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/arrest.

10 Note: The number of prison sentences is much lower when compared to jail sentences and therefore more likely to be impacted by statistical noise or case composition than by intentional decisions by judges.

11 Drug offenses continue to be involved in a large percentage of the state’s overall prison admission when compared to 2019 (27.6% vs. 31.0%), overall admissions where drugs were the most serious offense (18.7% vs. 22.2%), and prison admissions on account of revocations from parole, probation, or extended supervision (22.1% vs. 23.6%). See Department of Corrections, Prison Admissions Dashboards: Offense, Department of Corrections (2023), https://doc.wi.gov/Pages/DataResearch/PrisonAdmissions.aspx.

12 STEVENS POINT, WIS., Schedule of Cash Deposits: Public Peace and Offenses, Ordinance § 24.27 (2023) (reducing punishment to $5 fine); KENOSHA, WIS., Possession of Marijuana, Ordinance # 11.146 (2023) (reducing punishment for possession under 28 grams to $10); MILWAUKEE COUNTY, WIS., Possession and Use of Marijuana, Ordinances # 24.01, 24.02 (2023) (reducing fine to no more than $1).

13 Counties were considered urban if they are included in either a micropolitan or metropolitan statistical area by the Census Bureau. All other counties were considered rural. See United States Census Bureau, Wisconsin: 2020 Core Based Statistical Areas and Counties, United States Census Bureau (2020), https://www2.census.gov/programs- surveys/metro-micro/reference-maps/2020/state-maps/55_Wisconsin_2020.pdf.

14 We cannot prove this theory with our limited data, but it is a likely explanation because the potential punishments for possession with intent are the same as for manufacturing or delivering cannabis, but the first does not require actual intent to manufacture or deliver but requires merely possession of the required amount of the substance. See Wis. Stat. § 961.41 (2023).

15 We made an intentional decision to exclude counties that border Minnesota from being classified as a “border county” because that state legalized cannabis in a year after which we have data available. Dane and Milwaukee counties were intentionally excluded from the category of non-border counties because they differ so significantly from the border counties and other non-border counties on cultural, demographic and population factors that we are unable to control for given the data available.

16 This number reflects a change so low in raw numbers (1 vs. 0) that it merely could be on account of statistical noise rather than an actual reduction in prison sentences.

17 Department of Corrections, Persons in our Care: 12/30/2022, Department of Corrections (2022), available at https://doc.wi.gov/Pages/DataResearch/DataAndReports.aspx; Department of Corrections, Persons in our Care: 12/27/2019, Department of Corrections (2019), available at https://doc.wi.gov/Pages/DataResearch/DataAndReports.aspx.

18 Department of Corrections, supra note viii (showing that there was a total of 7,179 admissions during 2022).

19 Specific cost savings are $602,841 and $67,270. These reflect the real cost of the sentence imposed during 2022 minus any prison or extended supervision time that ran concurrently to offenses not involving cannabis. The data and more methodological details are available upon request from the author.

Wisconsin’s Department of Corrections reports that the most recent annual cost for each male incarcerated is $43,843; for each female, it is slightly more at $53,271. It also reports that extended supervision cost $9.70 per day or $3,540.50 per year. See Division of Adult Institutions, Corrections at a Glance, Department of Corrections (2023), available at https://doc.wi.gov/Pages/DataResearch/DataAndReports.aspx; Wisconsin Department of Corrections See Division of Community Corrections, Corrections at a Glance, Department of Corrections (2023), available at https://doc.wi.gov/Pages/DataResearch/DataAndReports.aspx.

20 The total budget for Wisconsin’s corrections department during fiscal year 2023 is $ 1,504,512,900. See S.B. 70 § 20.410 (2023), available at https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2023/proposals/SB70.

The post Criminal Enforcement of Marijuana Laws Uncommon in Many Wisconsin Counties appeared first on Badger Institute.