This post originally appeared at https://www.badgerinstitute.org/deeply-rural-millville-isnt-coming-back-and-likes-it-that-way/

A pioneering village, slowly fading since the Civil War, opts to stay undeveloped. Second in a series of profiles of persevering small towns in the Badger State.

A crescent moon glowing like an ember hangs low over a bluff, lighting the southwestward path of the Wisconsin River on its way to the Mississippi.

Just after dusk, what was long ago a churning Town of Millville center goes dark. One by one, lights appear in homes scattered among a maze of bluffs rising up all around Mill and Warner creeks, which merge and empty into a Wisconsin River slough.

The people in those homes, if they aren’t retired, probably work in Prairie du Chien, 14 miles west, or maybe Fennimore, 17 miles to the east. There are no businesses of any kind left in Millville.

And because of state Department of Natural Resources wildlife preservation policies and the State Farmland Preservation Act, passed back in 1977, it isn’t likely this town on Grant County’s northern border will have any new ones soon — or ever.

Larry Koschkee, who probably loves Millville more than any person alive, is also in part to blame for smothering its development. Koschkee was the chair of a planning commission that understood the intention of the Farmland Preservation Act and in 1990 required that all land sales be 35 acres or more.

The act’s purpose was to keep property taxes low for farmers and keep farmable land from being broken up and converted into residential subdivisions.

By then it was clear to Koschkee and other town leaders that what was the heart of a flourishing town before the Civil War wasn’t coming back. They made a commitment to the remaining farmers and the residents who loved the rugged creek-fed land almost hidden by the bluffs.

“It’s kind of a sad story in one respect, because a lot of people aren’t fortunate enough to live here,” Koschkee says, looking at the moon from his pickup truck. “I felt kind of selfish, protecting what I have, but the town is unique in its rural makeup.”

There is a uniqueness to each of the small, rural towns in Wisconsin, many of which long ago flourished because of waterways or trains or particularly verdant farmland or ancient timber — many of which are also slowly shrinking but persevering due to strong community bonds or, at times, government policy. Sometimes both.

In an effort to better understand why some flourish and others die, the Badger Institute is publishing occasional profiles.

As we pointed out in our first story in December, of the 1,939 municipal units that make up the state, 116, or nearly 6%, have lost more than 20% of their populations since 1990. More than half — 1,000 — of these units have populations of fewer than 1,000 people and 420 of those have fewer than 500 residents.

Millville’s population was 92 in 2020, according to U.S. Census data — down from 169 in 1990, a 45.6% loss. Only the Town of Jacobs in Ashland County, which had a 56.8% drop, lost more people over that period.

The 2020 Census figures illustrate what happens when a community commits in its land policy to agriculture while fewer people make a living farming in Wisconsin.

In 2012, the Millville Town Board voted to replace the 35-acre land sales threshold, allowing property owners to sell at any one time only one acre of land for every 20 they own. The new owners may build or develop on the land, but only if the town board and the Grant County Board of Supervisors approve a change in the agricultural zoning, Koschkee says. This change was in keeping with the state and county land plans to preserve the agricultural and natural character of the town.

Millville today doesn’t attract many younger or wealthier Wisconsinites.

The median age is 60, and nearly 40% of its 92 residents are 65 or older.

The median income of $60,313 is well below the state’s $71,133 average, and more than 13% of Millville’s population meet the standard for poverty set by the federal government.

Koschkee, the 79-year-old unofficial, but undisputed, town historian, hasn’t officially lived in Millville since 1995. He makes a 90-minute trip from his home in Monroe to camp in what he calls his 10- by 16-foot “shed” on two acres of land and otherwise check on things.

He has a daughter living in New Mexico who has no use for a little patch of land deep in rural Wisconsin. “Someday, I guess we’re going to break the Koschkee chain of ownership,” he says.

Koschkee came late to his family genealogy and the town’s history. On the paternal side, the Koschkees had come to what was once known as Warner’s Landing in the 1850s. In a short history he wrote for the Grant County Genealogical Society, he tells of Ameal Koschkee’s stage line between Millville and Fennimore in the late 1870s. By 1910, the Koschkees were gone.

But the fuse was lit. “When I found out about it and came back, I fell in love with the place,” Koschkee says. He bought 45 acres of farmland in 1988. He bought a house in another part of the town in 1989 and sold it in 1995. He built a log cabin on the farmland in 1997 and sold it 20 years later, the same year he bought the two acres he still owns.

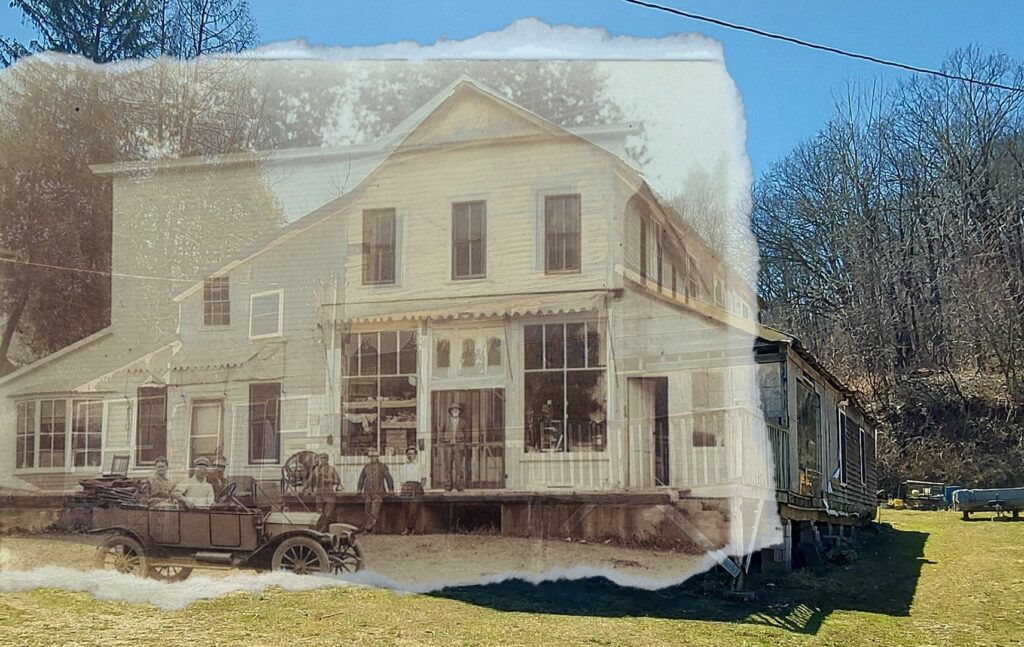

Even in good light you have to squint hard to see Millville the way it was, the way Koschkee sees it. Driving around on the gravel roads that track the more than three dozen creeks in the area, stopping at landmarks only he knows, the place comes alive.

Koschkee stops along County Road C at Warner’s Landing, where in April 1838 a keelboat named Kickapoo delivered the first four families from Ohio who took advantage of a land sale at 50 cents an acre.

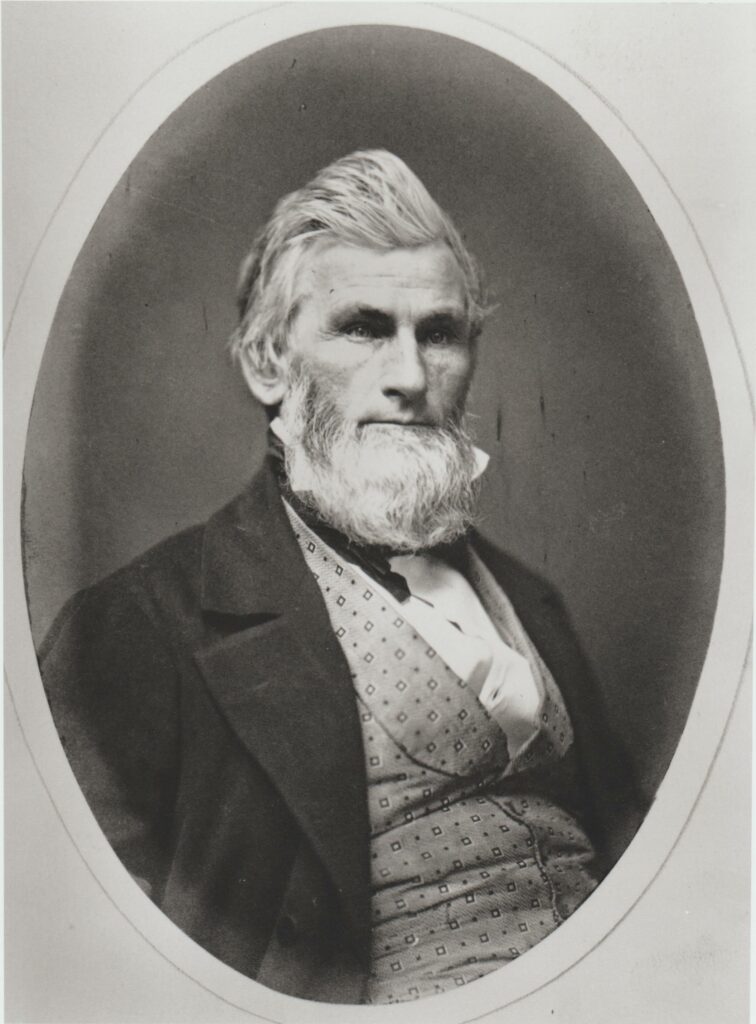

Elihu Warner and his son, Jared, after whom one of the main creeks is named, were the drivers of what would soon be a little boom town. Jared was a town chair and was later elected to the state Legislature. “Fascinating as to what he accomplished in his lifetime,” Koschkee says. “Someone should write his story.”

At the place where Millville and Warner Creeks meet, Koschkee points to where the Warners built the first sawmill in 1839. Over the next 15 years, there would be six mills on the water, sawmills, a grist mill, a feed mill and a woolen mill. Shops, stores and schools followed.

For decades after that, little or nothing happened in Millville. “Like a lot of little towns, the Civil War was the downfall of Millville,” Koschkee says. “Young men went off to war and they didn’t come back.”

There is no trace of much of what went on then. Koschkee points to a portion of a building that once was a creamery built in 1895. On the other side of the road is the Henry Horsfall general store, that had been turned into apartments, but hasn’t been lived in for 40 years. The Millville Methodist Church, also built in 1895, still stands, with a bell that still rings and serves as the Town Hall.

Source: WI DNR, Bureau of Facilities and Land

The DNR now owns about 40% of the Town of Millville. It made its first land purchase for wildlife preservation along the Wisconsin River in the 1970s. Just west of Millville, at the Mississippi River, is more than 2,600 acres of state-owned Wyalusing State Park.

Given all the state and local restrictions on campers, travel trailers and houses, only a certain kind of person or family wants to be in Millville. No one grandfathered in, such as Koschkee, is clamoring for some kind of economic revival.

“The property owners like the isolation,” Koschkee says, pulling up to the Town Hall. “But there is a heartbeat here, yet.”

Mark Lisheron is the Managing Editor of the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited. Photographs courtesy of Larry Koschkee.

var gform;gform||(document.addEventListener(“gform_main_scripts_loaded”,function(){gform.scriptsLoaded=!0}),window.addEventListener(“DOMContentLoaded”,function(){gform.domLoaded=!0}),gform={domLoaded:!1,scriptsLoaded:!1,initializeOnLoaded:function(o){gform.domLoaded&&gform.scriptsLoaded?o():!gform.domLoaded&&gform.scriptsLoaded?window.addEventListener(“DOMContentLoaded”,o):document.addEventListener(“gform_main_scripts_loaded”,o)},hooks:{action:{},filter:{}},addAction:function(o,n,r,t){gform.addHook(“action”,o,n,r,t)},addFilter:function(o,n,r,t){gform.addHook(“filter”,o,n,r,t)},doAction:function(o){gform.doHook(“action”,o,arguments)},applyFilters:function(o){return gform.doHook(“filter”,o,arguments)},removeAction:function(o,n){gform.removeHook(“action”,o,n)},removeFilter:function(o,n,r){gform.removeHook(“filter”,o,n,r)},addHook:function(o,n,r,t,i){null==gform.hooks[o][n]&&(gform.hooks[o][n]=[]);var e=gform.hooks[o][n];null==i&&(i=n+”_”+e.length),gform.hooks[o][n].push({tag:i,callable:r,priority:t=null==t?10:t})},doHook:function(n,o,r){var t;if(r=Array.prototype.slice.call(r,1),null!=gform.hooks[n][o]&&((o=gform.hooks[n][o]).sort(function(o,n){return o.priority-n.priority}),o.forEach(function(o){“function”!=typeof(t=o.callable)&&(t=window[t]),”action”==n?t.apply(null,r):r[0]=t.apply(null,r)})),”filter”==n)return r[0]},removeHook:function(o,n,t,i){var r;null!=gform.hooks[o][n]&&(r=(r=gform.hooks[o][n]).filter(function(o,n,r){return!!(null!=i&&i!=o.tag||null!=t&&t!=o.priority)}),gform.hooks[o][n]=r)}});

Submit a comment

“*” indicates required fields

/* = 0;if(!is_postback){return;}var form_content = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘#gform_wrapper_21’);var is_confirmation = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘#gform_confirmation_wrapper_21’).length > 0;var is_redirect = contents.indexOf(‘gformRedirect(){‘) >= 0;var is_form = form_content.length > 0 && ! is_redirect && ! is_confirmation;var mt = parseInt(jQuery(‘html’).css(‘margin-top’), 10) + parseInt(jQuery(‘body’).css(‘margin-top’), 10) + 100;if(is_form){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).html(form_content.html());if(form_content.hasClass(‘gform_validation_error’)){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).addClass(‘gform_validation_error’);} else {jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).removeClass(‘gform_validation_error’);}setTimeout( function() { /* delay the scroll by 50 milliseconds to fix a bug in chrome */ }, 50 );if(window[‘gformInitDatepicker’]) {gformInitDatepicker();}if(window[‘gformInitPriceFields’]) {gformInitPriceFields();}var current_page = jQuery(‘#gform_source_page_number_21’).val();gformInitSpinner( 21, ‘https://www.badgerinstitute.org/wp-content/plugins/gravityforms/images/spinner.svg’, true );jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_page_loaded’, [21, current_page]);window[‘gf_submitting_21’] = false;}else if(!is_redirect){var confirmation_content = jQuery(this).contents().find(‘.GF_AJAX_POSTBACK’).html();if(!confirmation_content){confirmation_content = contents;}setTimeout(function(){jQuery(‘#gform_wrapper_21’).replaceWith(confirmation_content);jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_confirmation_loaded’, [21]);window[‘gf_submitting_21’] = false;wp.a11y.speak(jQuery(‘#gform_confirmation_message_21’).text());}, 50);}else{jQuery(‘#gform_21’).append(contents);if(window[‘gformRedirect’]) {gformRedirect();}}jQuery(document).trigger(‘gform_post_render’, [21, current_page]);gform.utils.trigger({ event: ‘gform/postRender’, native: false, data: { formId: 21, currentPage: current_page } });} );} );

/* ]]> */

The post Deeply rural Millville isn’t coming back — and likes it that way appeared first on Badger Institute.